His standing among Indian military leaders is the same as that of Patton in the US Army, and of Rommel in the Wehrmacht.

A brilliant tactician and strategist, he was known for his unconventional and creative manoeuvres, which are the key to success in battle. Tales about his wartime exploits abound, and are studied by students in military training institutions.

Though he did not reach the top of the military ladder, he is better known than many who did.

He was the most successful Corps Commander during the 1971 Indo-Pak War, but surprisingly, he was given neither a decoration, nor a promotion.

One of the few JCOs to receive a commission and then leave a legacy unparalleled in India. He was a difficult subordinate, and his penchant for the unconventional, and scant regard for rules and regulations, acted as obstacles in his career. Viewed purely from the military angle, Sagat's performance as a combat leader was par excellence.

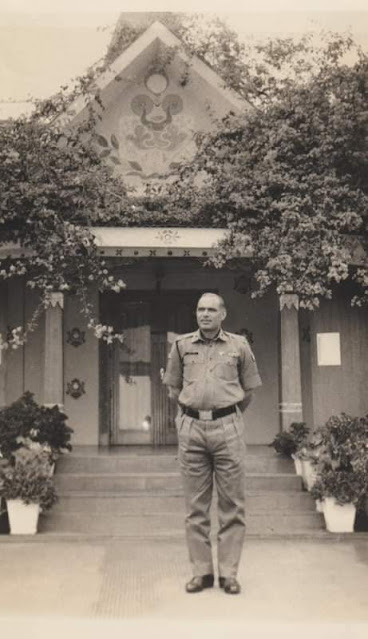

Lieutenant General Sagat Singh is one of India's most brilliant and audacious military leaders. Though not as well known as some of his contemporaries, his record as a combat leader is unmatched. He not only succeeded in every operation, but went beyond, and achieved more than what he was asked to do. Imbued with an aggressive spirit, and the ability to take risks, he is the epitome of the combat leader, who leads from the front.

Sagat was born on 14 July 1919, in Bikaner. His father, Thakur Brij Pal Singh, was a Rathore Rajput, from the vassalage of Bikaner, which was one of the important Indian states ruled by the Rathores, the other being Marwar (Jodhpur). He was serving in the famous Camel Corps of Bikaner, and fought in World War I, in Mesopotamia, now called Iraq. Sagat was the eldest of three brothers, and had his early education in Walter Nobles' School, in Bikaner. After school, he joined Dungar College, in Bikaner. However, he did not finish his graduation, and after passing the Intermediate examination, joined the Bikaner State Forces.

Soon after World war II started, Sagat joined the IMA, as an Indian State Forces Cadet. After passing out in 1941, he went back to the Bikaner State Forces, after a short attachment with a British battalion, the South West Borders, which was then at Bannu, in the North West Frontier Province. He joined the Bikaner State Forces at Secunderabad, from where it moved to Chaman, on the Frontier, and later to Faizabad, in the United Provinces. Finally, in October 1941, the unit was ordered to move to Iraq, to suppress the Rashid Ali revolt. After a few months in Iraq, the unit was moved to Kut-el-Amara, and then to Syria, and Palestine, before returning to Iraq, as part of 6 Indian Division. In 1943, he was nominated to attend the junior staff course at the Staff College, at Haifa.

When Sagat reported to the Staff College, he found that the waiters serving in the mess were all Italians, and did not understand English. Sagat asked the British Major, an old re-employed officer who was in charge of the mess, to pass instructions that he should not be served beef. The Major called the Staff Sergeant, and began to pass the orders. The Sergeant nodded his head, and told Sagat not to worry, since the waiters knew about the eating habits of Indians, as they had one on the previous course. When Sagat was served his first meal, he thought the meat did not look like mutton. When he asked a colleague, he was informed that it was indeed beef. After a great deal of expostulation, it was discovered that the 'Indian' on the previous course was the son of Sir Sikander Hayat Khan. The waiters had been told that he did not pork, and they had assumed that Sagat, being an Indian, would have the same preferences.

To be on the safe side, Sagat decided to stay away from meat altogether, and remained a vegetarian for the rest of his stay at Haifa.

The course at Haifa, though of seven months duration, was called the junior staff course, and not equated to the full staff course, at Camberley or Quetta. In 1945, he was nominated on the staff course, at Quetta, and thus had the chance to attend two staff courses, within three years. After the course, Sagat returned to Bikaner, to join his unit. However, after the merger of the Indian States with the Indian Union in 1947, he decided to opt for the Indian Army. His application was accepted, and on 15 January 1949, he was granted a permanent commission in the Indian Army. His service in the Bikaner State Forces was counted, and he was given the seniority from 27 October 1941, and assigned to the 3rd Gorkha Rifles. Since he was one of the few officers in the Indian Army who had done the staff course, he was posted to HQ Delhi Area, as GSO 2 (Ops). The GOC was Major General Tara Singh Bal, and the tactical HQ was in the Red Fort.

After a short tenure at Delhi, Sagat was posted as Brigade Major to 168 Infantry Brigade, which was then in Chhamb. From this appointment, he was reverted to regimental service in 1954, and posted as second-in-command, 3/3 Gorkha Rifles, then being commanded by Lieut-Colonel P.S. Thapa. The battalion was located at Bharatpur, in Rajasthan, which was Sagat's home state. In November 1954, it moved to Dharamsala, as part of a brigade which was under the command of Brigadier (later Lieut General) P.O. Dunn, who was from the same regiment, and had commanded 1/3 Gorkha Rifles earlier.

In February 1955, Sagat was promoted Lieut Colonel, and given command of 2/3 Gorkha Rifles, which was then at Ferozepore, in the Punjab. He relieved Lieut Colonel Nand Lal Kapur, who had come to the regiment from the Rajputana Rifles. Before Independence, Gorkha regiments were officered only by the British, and no Indians had been permitted. In fact, there was a general feeling among British officers that Gorkha troops would refuse to serve under Indian officers. After Independence, four of the ten Gorkha regiments were transferred to the British Army, while the rest remained in India. However, all Gorkha soldiers were given the choice, to serve in the British or the Indian Army. It came as a surprise to the British that 90 per cent opted to serve in India, under Indian officers. The 2nd, 6th, 7th and 10th Gurkhas became part of ' The Brigade of British Gurkhas'. The 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 8th and 9th Gurkhas remained in the Indian Army, and were renamed the 'Gorkhas', which was their correct ethnic name. Officers from other regiments of the Indian Army were posted to replace the British officers, who left for home. The majority came from the regiments which had been transferred to Pakistan, such as the Frontier Force and the Baluch Regiment.

2/3 Gorkha Rifles was then part of 167 Infantry Brigade, which was being commanded by Brigadier Badshah. In October 1955, the battalion moved to Jammu, and soon thereafter, Sagat was nominated on the Senior Officers Course, at the Infantry School, Mhow. In December 1955 he handed over command to Lieut Colonel J.P. D'Cunha, who came from his erstwhile battalion, 3/3 Gorkha Rifles. After completing the Senior Officers Course, on which he was an awarded an instructors' grading, Sagat was posted as CO 3/3 Gorkha Rifles, in which he had served as the second-in-command. The CO of 3/3 GR had been removed in February 1956, and the second-in-command, Major P.J. Heffernon was officiating, till Sagat assumed command in April 1956. It was still located at Dharamsala, and Sagat set about improving the standard of training and morale, in right earnest. As a result, the battalion performed exceedingly well, and won the divisional competitions in football, boxing, and skill-at-arms. During an exercise, while performing the role of Advance Guard, it moved at such a blistering pace that the Corps Commander, Lieut General (later General) J.N. Chaudhury, commented, " The rate of advance by the Advance Guard was so rapid that it could not be accepted as normal for planning purposes."

An interesting incident which occurred during Sagat's command was the 'khud race' (khud, loosely translated, means a valley, or steep incline; a khud race is a cross country race, across hills and valleys). 3 Sikh was located nearby, and there was great rivalry between the two battalions, in games and sports. One day, the CO of the Sikhs remarked that his boys could out pace the Gorkhas, anytime, and challenged them to a 'khud race'. He had probably said it as a joke, but Sagat took up the challenge seriously. On the day of the race, he invited the Corps Commander, in addition to the Divisional and Brigade Commanders. Also present was Justice G.D. Khosla, of the Punjab High Court. The Gorkhas won the race, and the Corps Commander said, "Well, there is no doubt as to who is superior up and down the hills." As for Justice Khosla, it was an unique experience, and he remarked, "It is the most thrilling sport I have ever seen. To see a Gorkha coming down the hill is a pleasure indeed."

The battalion moved to an operational area in the Poonch Sector, in Jammu and Kashmir, in August 1957. In November 1957, Sagat handed over command of 3/3 Gorkha Rifles to Lieut Colonel P. Raghavan, and proceeded to the Infantry School, where he had been posted as a Senior Instructor. After spending about a year as Senior Instructor, Sagat was appointed GSO 1, in the Training Team. He was now responsible for preparation of the training material, used for instruction. This involved revision of outdoor as well as indoor exercises, and updating the syllabus, to incorporate new concepts and tactical doctrine. In 1959, he was promoted Colonel, and posted to Delhi, as Deputy Director, Personnel Services, in the Adjutant General's Branch, at Army HQ. He now had to deal with a large number of subjects, such as pay, pension, ceremonials, welfare , terms and conditions of service, etc. He replaced Colonel (later Major General) D.K. 'Monty' Palit, who was promoted, and given command of a brigade.

After a short stint in Delhi, Sagat was promoted Brigadier, and given command of 50 Parachute Brigade, at Agra, in September 1961. This was unprecedented, since he was not a paratrooper, and would have to earn his 'wings', before he could become one. He was then over 40 years old, and few people had started jumping at that age. But Sagat knew that he had to get the coveted 'wings,' before he was accepted in the fraternity of paratroopers, and could wield any authority. He had to undergo the tough probation course, before he could begin his jumps. To save time, he sometimes did two jumps a day, and got his 'wings' in record time. For a person of his age, it was no mean achievement. Para troopers place a high premium on courage and physical toughness, and this improved his stock in the brigade as nothing else could have done. At that time, 50 Parachute Brigade had only two battalions, 1 Para and 2 Para, with the latter having recently joined the formation from Jammu and Kashmir. To get to know his command, and gauge the state of training, Sagat set tactical exercises for both battalion groups. This turned out to be fortuitous, since 2 Para was subsequently given an operational task of a similar kind, except for the riverine obstacles, in Goa.

It was while commanding 50 Parachute Brigade that Sagat really flowered, and his genius as a combat leader came to the fore. During the Goa operations, he displayed tactical brilliance, and the ability to seize opportunities in battle, which few commanders are gifted with. Sagat proved the adage that in war, the timorous rarely succeed, while the bold invariably triumph, even against heavy odds. The story of his exploits during the operations is now part of the Indian Army's folk lore, and is often quoted as an example to students of military science.

Though the result of the operations in Goa was along expected lines, the speed of the Indian advance surprised many observers. The credit for this goes to Sagat, and his troops, who exceeded their brief, and managed to reach Panjim, which they had not been asked to do. The fact that 17 Infantry Division, in spite of the vastly superior resources at their disposal, and almost no opposition from the enemy, could make little headway, goes to show that the going was not easy. If the paratroopers succeeded, it was because of better fighting spirit, morale and leadership. The ability to take risks, and seize fleeting opportunities is the hall mark of a successful military leader, and Sagat proved beyond doubt that he had these qualities in ample measure. The failure of Indian troops, barely a year afterwards when facing the Chinese, only underlined the point that irrespective of the fighting capabilities of the soldier, it is the quality of leadership which tilts the balance, in war.

In January 1964, Sagat handed over command of 50 Para Brigade to Brigadier A.M.M. Nambiar, and proceeded to attend the fourth course, at the National Defence College, in Delhi. After spending a year on the course, he was posted as Brigadier General Staff 11 Corps, in January 1965. He served in this appointment for just six months, and in July 1965, was promoted Major General, and posted as GOC 17 Mountain Division, replacing Major General Har Prasad. The division was then in Sikkim, and soon after he took over, there was a crisis. In order to help Pakistan during the 1965 War, the Chinese served an ultimatum, and demanded that the Indians withdraw their posts at Nathu La and Jelep La. According to the Corps HQ, the main defences of 17 Mountain Division were at Changgu, while Nathu La was only an observation post. In the adjoining sector, manned by 27 Mountain Division, Jelep La was also considered an observation post, with the main defences located at Lungthu. In case of hostilities, the divisional commanders had been given the authority to vacate the posts, and fall back on the main defences. Accordingly, orders were issued by Corps HQ to both divisions to vacate Nathu La and Jelep La.

Sagat did not agree with the views of the Corps HQ. Nathu La and Jelep La were passes, on the watershed, which was the natural boundary. The MacMahon Line, which India claimed as the International Border, followed the water shed principle, and India and China had gone to war over this issue, three years earlier. Vacating the passes on the watershed would give the Chinese the tactical advantage of observation and fire, into India, while denying the same to our own troops. Nathu La and Jelep La were also important because they were on the trade routes between India and Tibet, and provided the only means of ingress through the Chumbi Valley. Younghusband had used the same route during his expedition, sixty five years earlier, and handing it over to the enemy on a plate was not Sagat's idea of sound military strategy. Sagat also reasoned that the discretion to vacate the posts lay with the divisional commander, and he was not obliged to do so, based on instructions from Corps HQ.

As a result of orders issued by Corps HQ, 27 Mountain Division vacated Jelep La, which the Chinese promptly occupied. However, Sagat refused to vacate Nathu La, and when the Chinese became belligerent, and opened fire, he also opened up with guns and mortars, though there was a restriction imposed by Corps on the use of artillery. Lieut-General (later General) G.G. Bewoor, the Corps Commander, was extremely annoyed, and tried to speak to Sagat, to ask him to explain his actions. But Sagat was not in his HQ, and was with the forward troops. So it was his GSO 1, Lieut Colonel Lakhpat Singh, who bore the brunt of the Corps Commander's wrath.

The Chinese had installed loudspeakers at Nathu La, and warned the Indians that they would suffer as they did in 1962, if they did not withdraw. However, Sagat had carried out a detailed appreciation of the situation, and reached the conclusion that the Chinese were bluffing. They made threatening postures, such as advancing in large numbers, but on reaching the border, always stopped, turned about and withdrew. They also did not use any artillery, for covering fire, which they would have certainly done if they were serious about capturing any Indian positions. Our own defences at Nathu La were strong. Sagat had put artillery observation posts on adjoining high features called Camel's Back and Sebu La, which overlooked into the Yatung valley for several kilometres, and could bring down accurate fire on the enemy, an advantage that the Chinese did not have. It would be a tactical blunder to vacate Nathu La, and gift it to the Chinese. Ultimately, Sagat's fortitude saved the day for India, and his stand was vindicated, two years later, when there was a show down at Nathu La. Today, the strategic pass of Nathu La is still held by Indian troops, while Jelep La is in Chinese hands.

In December 1967, Sagat was posted as GOC 101 Communication Zone Area, in Shillong. He had been serving in a non family station for almost two and a half years, and deserved a peace posting. He had requested for a posting to Delhi, and had been told that he would be sent to Army HQ, as Director of Military Training. So he was surprised when he was posted, and asked to move post haste, to 101 Communication Zone Area, which was involved in counter insurgency operations, against Mizo hostiles. He came to know later the Army Commander, Sam Manekshaw, had specifically asked for him, to sort out the Mizo Hills problem. Sagat had no choice, and accepted the assignment, like a good soldier.

The Mizo Hills (the area was given statehood and renamed Mizoram in 1971) lay in the North East of India. It was bounded by foreign territory on three sides - Burma (now Myanamar) in the East and South, and East Pakistan (now Bangla Desh) in the West. In the North, it touched Manipur and Tripura, as well as Assam, the state of which all these territories then formed a part. The Mizos have close racial links with the Chins, of Burma. They are a hardy tribe of hill people, who love their freedom. They were being supplied with arms and ammunition by East Pakistan, which encouraged them to raise the banner of revolt against India, and ask for freedom. They had formed a parallel government, and the Mizo National Army (MNA) had invested the Southern part of the Mizo Hills. The Border Security Force and the Assam Rifles, which were operating in the area, could not control the situation, and in 1966, the Army was inducted.

Shortly before Sagat's posting to 101 Communication Zone Area, a mixed Naga Mizo gang had been formed in Manipur, with a the aim of collecting weapons and ammunition from East Pakistan. The gang attacked a platoon outpost of 16 Jat, and after inflicting heavy casualties, got away with their weapons and ammunition. The gang then advanced towards Burma, and ambushed a company column of 8 Sikh, inflicting heavy casualties, and taking away their weapons. It then overran a platoon outpost of 30 Punjab, and took their weapons also. Subsequently, the gang ambushed a column of 2/11 Gorkha Rifles, and another of 5 Para, before crossing over into Burma. It was at this juncture that Sagat was asked to take charge, and retrieve the situation.

Soon after taking over, Sagat decided to visit the battalions, to assess the situation at close quarters. He visited every battalion deployed in the Mizo Hills, spending a night with each, sleeping on the ground. After talking to everyone, and analysing the encounters that had taken place, he was able to pin point three major reasons for the reverses suffered by our troops. These were lack of intelligence, lack of attunement of the infantry battalions to insurgency situations, and ill treatment of the locals, by a few post commanders. Sagat immediately set about the task of remedying these weaknesses, and issued directions towards this end.

In his typical style, he devised his own intelligence gathering system, by compromising some of the important executives in the organisation of the hostiles. Instead of sending them to jail, they were kept near the base at Aizwal, where Sagat had already moved his tactical headquarters. Their families were brought there, and they began to help our troops by giving intelligence reports, identifying hostiles during cordon and search operations, and translating captured documents. He also realised that the underground hostiles must be having their own systems for getting information, and passing orders. From the few letters that had been recovered by the battalions, he was able to get the stationery, letter heads and seals used by the hostiles, and had them copied in Calcutta. Information about the organisation and routine of messengers was gathered. Thereafter, small ambushes were laid, the messenger was intercepted, his bag searched, and his papers replaced with fakes.

The next problem was to adjust the training of the infantry battalions to suit the peculiar requirements of counter insurgency operations. An ad hoc training camp was started with a few officers who had been serving in the area for long, and had experience of fighting the hostiles. This later became the Counter Insurgency and Jungle Warfare School, at Vairangte. All units which were inducted into the area, first had to undergo an orientation course at this school. This proved very useful, and resulted in considerable reduction in casualties to troops. Today, it is one of the premier training establishments of the Indian Army, which trains officers, as well as entire units, in jungle warfare, and counter insurgency techniques.

Sagat realised that ethnic and linguistic differences alone do not cause rebellion. More often than not, it is repression and neglect of minorities which result in discontent, leading to an uprising. He issued strict orders against harassment and ill treatment of the population, and exemplary punishment was meted out to erring post commanders. In order to remove the feeling of neglect by providing food, medical care and other facilities, and also to improve security, Sagat decided to group the villages, astride the only road in the region, between Aizwal and Lungleh. There were strong objections from the civil administration, on legal and administrative grounds, but Sagat was able to overcome these hurdles, and carried out the grouping, as planned. Fortunately, he had developed excellent rapport with Mr. B.P. Chalia, the Chief Minister, and Mr. B.K. Nehru, the Governor of Assam, and this enabled him to have his way.

Being a paratrooper, Sagat knew the value of helicopters, and made extensive use of them, in Special Helicopter Borne Operations (SHBOs). These were mounted at short notice, when there was a tip off by an agent, and enabled troops to reach and intercept guerrilla bands in remote areas, as soon as their presence was detected. This experience was to pay rich dividends a few years later, during the operations for the liberation of Bangla Desh. By the time Sagat left Mizo Hills, peace had returned, with all hostile gangs either being liquidated, or having taken shelter in East Pakistan. In recognition of his splendid performance in controlling the insurgency in Mizo Hills, Sagat was awarded the PVSM, the highest non gallantry award for soldiers in India.

After a long tenure of three years, Sagat was promoted Lieut General in November 1970, and given command of 4 Corps, which had its headquarters at Tezpur. This was his third tenure in the East, in succession. By this time, Sam Manekshaw had taken over as COAS, and it was again at his behest that Sagat was chosen for this assignment. It proved to be a serendipitous choice, since 4 Corps, under Sagat's command, was to play a pivotal role, a year later. The liberation of Bangla Desh in 1971 was one of the Indian Army's finest hours. The lightning campaign, lasting just fourteen days, resulted in the total annihilation of Pakistani forces, and a magnificent victory for India. There were many acts of valour, and of fortitude in the face of adversity. Units and sub units fought with courage, dash and elan, and there was not a single reported incident of loss of morale, or cohesion. More than individual or collective gallantry, the unique feature of the campaign, and the one that proved decisive, was the quality of military leadership. Among the leaders whose contribution to the success of the operation was significant, was Sagat Singh. In fact, it was in 1971 that Sagat displayed, for the last time, his skills as a tactician, and conclusively proved his worth as a combat leader par excellence.

No comments:

Post a Comment